On this day in 1934, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow were ambushed by six policemen in rural Louisiana. The couple led the infamous Barrow Gang, notable for robbing banks, stores, and gas stations across several states. Over the course of two years, the gang killed nine police officers and several civilians, and they were labeled as public enemies.

Wanted poster for the Barrow Gang. Image courtesy of the Dallas Municipal Archives via Texas Heritage Online.

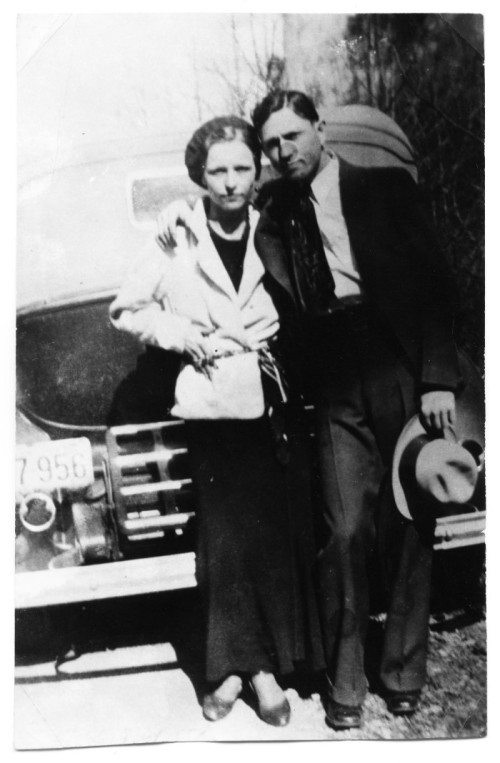

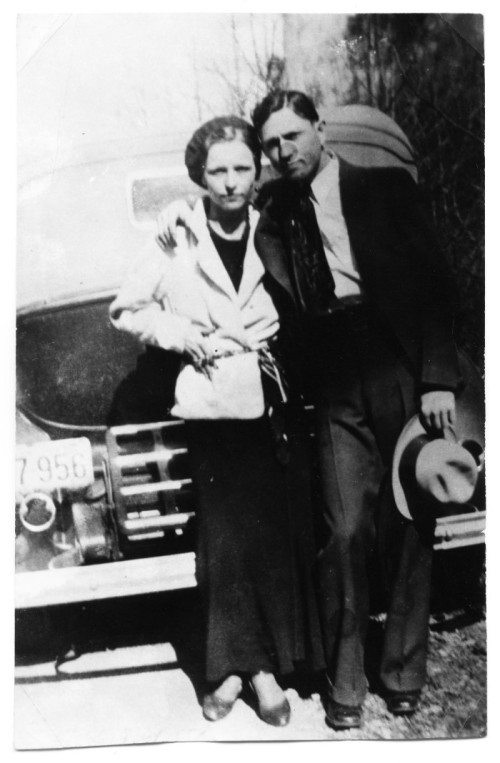

Their story gained national attention in 1933 when the gang escaped the police after a stand off at their hideout in Joplin, Missouri. In their hurry to flee the scene, the gang left nearly all their possessions behind, and the police discovered a camera with several roles of undeveloped film and poetry by Parker. The photographs depicted members of the gang posing in front of their car, often with firearms and cigars.

Photograph of Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker standing together behind their car. Image courtesy of the Dallas Municipal Archives via Texas Heritage Online.

Public fascination with the couple shortly turned to outrage after Barrow orchestrated a jailbreak in January 1934 followed by a series of murders in Texas and Oklahoma. After the jailbreak, Captain Frank Hamer, a former Texas Ranger, organized a posse of policemen who began tracking the outlaws’ movements through the winter and spring of that year. When it became clear that the group would soon visit one of the gang’s family members in Louisiana, the officers prepared an ambush. They concealed themselves in the bushes along a rural road, and began firing as soon as Clyde’s Ford V8 approached. They fired some 130 rounds at the car, killing both Bonnie and Clyde without offering a chance to surrender.

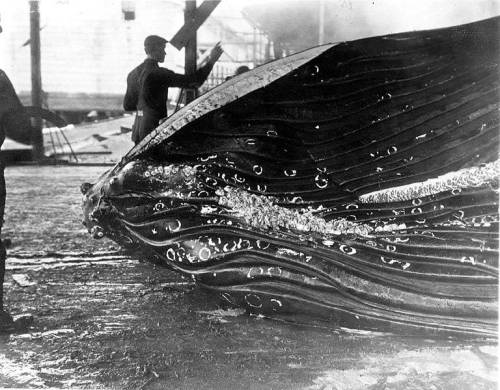

Officers inspect Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker’s bullet-riddled V8 Ford at the police impound after removing the couple’s bodies. Dallas County Sheriff Smoot Schmid is at left, hatless. Image courtesy of the Dallas Municipal Archives via Texas Heritage Online.

For more primary source materials related to Bonnie and Clyde, visit the Barrow Gang Collection at Texas Heritage Online. You can also find out more about the public enemies of the Great Depression era through Opening History.